Every child deserves the chance to read, write, and dream. Yet in Uganda, too many children complete their early years of primary school without achieving even the most basic literacy.

The 2023 National Assessment of Progress in Education (NAPE), conducted by the Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB), underscores the scale of the challenge. The survey, which tested P3 and P6 learners in literacy and numeracy, found that large numbers of children are struggling to acquire foundational reading and writing skills.

At P3, proficiency in literacy in English rose slightly from 49.9% in 2018 to 53.9% in 2023, while numeracy improved from 55.2% to 57.5%. At P6, numeracy proficiency also increased (from 50.9% to 58.0%), but literacy dropped sharply from 53.1% to just 42.7%. District-level gaps were stark: only four districts had at least 75% of their P6 learners proficient in literacy, while 48 districts had fewer than 25%. Children with special education needs and those in refugee-hosting schools scored consistently lower, pointing to the unequal realities learners face. From the report, slight gains in early grades are not translating into sustained literacy by the time children reach upper primary. And where a child lives, whether a refugee-hosting school or have special education needs, significantly shapes their chances of success.

1. Teacher quality remains a critical bottleneck

The NAPE survey confirms what many teachers themselves acknowledge. The fact that classroom instruction has phased out interactive methods that build comprehension and taken on rote memorization. While many teachers are committed, gaps in pre-service and in-service training mean they lack the practical skills needed to teach literacy effectively. In rural districts especially, teachers report being underprepared to use child-centered approaches. These challenges are compounded by low pay and poor working conditions, leading to high absenteeism. When teachers are absent or unprepared, children lose the consistent instruction they need to build strong foundations in the early grades.

2. Overcrowded classrooms limit individual support

Universal Primary Education (UPE) has been successful in raising enrollment, but the unintended consequence has been ballooning class sizes. In some schools, a single teacher may be responsible for 75 pupils, way above the recommended teacher-to-pupil ratio of 1:53. The NAPE findings show that such overcrowding leaves struggling readers with little or no individualized support, especially children with learning difficulties or those whose home language differs from the medium of instruction. Without plans to expand learning infrastructure, the cycle of low literacy achievement is unlikely to change.

3. Scarcity of reading materials holds learners back

The NAPE contextual data also highlights the lack of adequate reading materials in schools. Many pupils share a single textbook, and as we have found in some of our community engagements, 82% of children in the communities of Kisindizi, Kibembe and Kisoga have never owned a storybook. This scarcity deprives learners of opportunities to practice reading for pleasure, which is a critical factor in building fluency. Where materials do exist, they are usually in English, a language many P3 learners are still acquiring. Teachers believe that locally relevant, age-appropriate books would make literacy instruction more meaningful and effective. While NGOs and donor-funded programs like our library stocking project have stepped in to bridge the gap, sustainability and coverage are still a concern.

From assessment to action

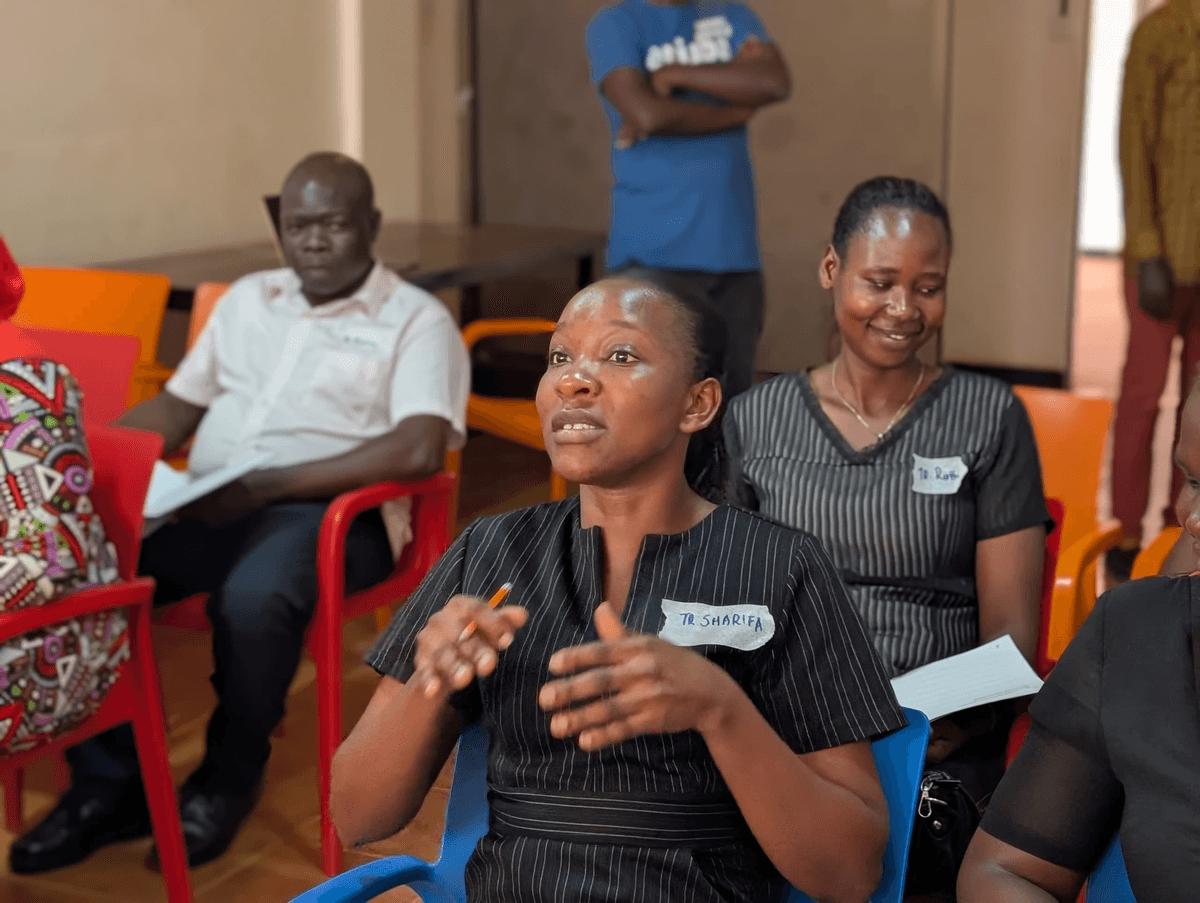

The NAPE survey does more than diagnose the problem; it also points to potential best practices. District-level stakeholders emphasized the importance of continuous professional development for teachers, peer-to-peer learning among educators, and stronger community engagement to support literacy outside the classroom.

For policymakers, this means making strategic investments that address the root causes of Uganda’s literacy crisis. First, teachers must be equipped with modern methods of literacy instruction, including training in the use of local languages at the early grades to ease children into reading. Second, classroom conditions need urgent improvement; reducing class sizes where possible and expanding school infrastructure so that every child can receive the attention they need. Finally, access to reading resources must be strengthened by building partnerships with publishers and community based organisations to ensure a sustainable supply of age-appropriate books in both English and local languages. Together, these investments can create the foundation for real, lasting progress in literacy.

Literacy is not just about passing exams. It is about equipping Uganda’s children with the skills to participate fully in society and the economy. Despite progress in access to education, too many children are being left behind in the most fundamental of skills. Addressing this silent crisis requires urgency, creativity, and above all, a commitment to placing literacy at the heart of Uganda’s education agenda.